Sustainability equates to a sustainable global society founded on respect for nature, universal human rights, economic justice, and a culture of peace.

Wednesday, January 25, 2012

We've Got Bigger Problems Right Now

Saturday, January 21, 2012

Permaculture In Damaged Lands: Degradation And Restoration In New Mexico

Friday, January 20, 2012

Governments Spend $1.4 Billion Per Day to Destabilize Climate

We distort reality when we omit the health and environmental costs associated with burning fossil fuels from their prices.

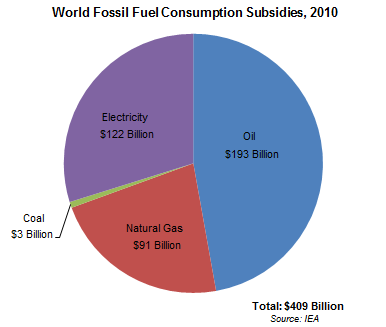

When governments actually subsidize their use, they take the distortion even further. Worldwide, direct fossil fuel subsidies added up to roughly $500 billion in 2010. Of this, supports on the production side totaled some $100 billion. Supports for consumption exceeded $400 billion, with $193 billion for oil, $91 billion for natural gas, $3 billion for coal, and $122 billion spent subsidizing the use of fossil fuel-generated electricity. All together, governments are shelling out nearly $1.4 billion per day to further destabilize the earth’s climate.

Kuwait’s fossil fuel subsidies were highest on a per capita basis, with $2,800 spent per person. The United Arab Emirates and Qatar followed, each spending close to $2,500 per person. More

Thursday, January 19, 2012

Amazon Basin shifting to carbon emitter, study says

The Amazon Basin, traditionally considered a bulwark against global warming, may be becoming a net contributor of carbon dioxide (CO2) as a result of deforestation, researchers said on Wednesday.

In an overview published in the journal Nature, scientists led by Eric Davidson of the Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts say the Amazon is "in transition" as a result of human activity.

Over 50 years, the population has risen from six million to 25 million, triggering massive land clearance for logging and agriculture, they said.

The Amazon's carbon budget - the amount of CO2 that it releases into the atmosphere or takes from it - is changing although it is hard to estimate accurately, they said.

"Deforestation has moved the net basin-wide budget away from a possible late 20th-century net carbon sink and towards a net source," according to their paper.

Mature forests such as the Amazon are big factors in the global-warming equation.

Their trees suck up CO2 from the atmosphere through the natural process of photosynthesis. But when they rot or are burned, or the forest land is plowed up, the carbon is returned to the air, adding to the greenhouse effect.

The paper estimates that the biomass of the Amazon contains a whopping 100 billion tonnes of carbon - the equivalent of more than 10 years of global fossil-fuel emissions.

Global warming, unleashing weather shifts, could release some of this store, it warned.

"Much of the Amazon forest is resilient to seasonal and moderate drought, but this resilience can and has been exceeded with experimental and natural severe droughts, indicating a risk of carbon loss if drought increases with climate change." Read more: http://www.ottawacitizen.com/technology/Amazon+Basin+shifting+carbon+emitter+study+says/6016986/story.html#ixzz1jw0zTDTn

Wednesday, January 11, 2012

Geopolitical Implications of “Peak Everything”

From competition among hunter-gatherers for wild game to imperialist wars over precious minerals, resource wars have been fought throughout history; today, however, the competition appears set to enter a new—and perhaps unprecedented—phase. As natural resources deplete, and as the Earth’s climate becomes less stable, the world’s nations will likely compete ever more desperately for access to fossil fuels, minerals, agricultural land, and water.

Nations need increasing amounts of energy and raw materials to produce economic growth, but the costs of supplying new increments of energy and materials are burgeoning. In many cases, lower-quality resources with high extraction costs are all that remain. Securing access to these resources often requires military expenditures as well. Meanwhile the struggle for the control of resources is re-aligning political power balances throughout the world.

This game of resource “musical chairs” could well bring about conflict and privation on a scale never seen before in world history. Only a decisive policy shift toward resource conservation, climate change mitigation, and economic cooperation seems likely to produce a different outcome. America’s Resource Geopolitics

The United States—the world’s current economic and military superpower— entered the industrial era with a nearly unparalleled endowment of natural resources that included an abundance not only of forests, water, topsoil, and minerals, but also of oil, coal, and natural gas. Like all other nations, the U.S. has approached resource extraction using the low-hanging fruit principle. Today its giant onshore reservoirs of conventional oil are largely depleted, and the nation’s total oil production is down by over 40 percent from its peak in 1970—despite huge discoveries in Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico. Its total coal resources are vast, but rates of extraction probably cannot be increased significantly and will likely begin to decline within the next decade or two. Unconventional hydrocarbon resources (such as natural gas liberated by the hydrofracking of shale deposits) are beginning to be commercialized, but come with high investment costs and worrisome environmental risks. U.S. extraction rates for many minerals have been declining for years or decades, and currently the nation imports 93 percent of its antimony, 100 percent of its bauxite (for aluminum), 31 percent of its copper, 99 percent of its gallium, 100 percent of its indium, over half its lithium, and 100 percent of its rare earth minerals. More

Tuesday, January 3, 2012

The end of the Keynesian era

In 1939, President Roosevelt’s Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau concluded: “[W]e have tried spending money. We are spending more than we have ever spent before and it does not work… I say after eight years of this Administration we have just as much unemployment as when we started.”

New York, NY - The beginning of the Keynesian Era can be dated, perhaps, to September 1931 - the year when Britain intentionally devalued the pound, throwing the world into turmoil and currency conflict.

Today, we are again in an extended period of economic crisis. However, I suspect that this will turn out to be the end of the Keynesian Era - the time when it is, in fact, Keynesianism itself which destroys us.

"Keynesianism" is really just this century's version of Mercantilism, which dates from the beginning of the 17th century. There's nothing particularly new or original about it. Behind the billows of academic obfuscation, it amounts to two policies: exaggerated government spending in the face of recession, and some sort of "easy money" policy. Although the term "Keynesian" has become unfashionable, virtually all academics and government economic advisers are Keynesians today.

The primary attraction of Keynesianism, I would say, is not its wonderful overall results, but rather, that it provides a good excuse for politicians do to what they wanted to do anyway. Any politician knows that a certain way to increase one's popularity is to hand out government money. In a recession, politicians are likely worried about their declining popularity, and thus their first instinct is to hand out more money. The Keynesian economists often boast that the money can be spent on total waste, such as "digging holes and filling them back up".

The other Keynesian trick is some form of "easy money" policy, which usually results in a decline in currency value. Currency devaluation can, in some cases, result in what appears to be a short-term improvement in economic conditions. However, it is said that "you can't devalue yourself to prosperity", and it is true. The countries that have the greatest success in the long term, also have the most stable, highest-quality currencies.

A basic effect of currency devaluation is to reduce real wages, since wages are paid in a devalued currency. This can increase "competitiveness", but it is easy to see that a strategy that reduces real wages cannot create long-term prosperity. More